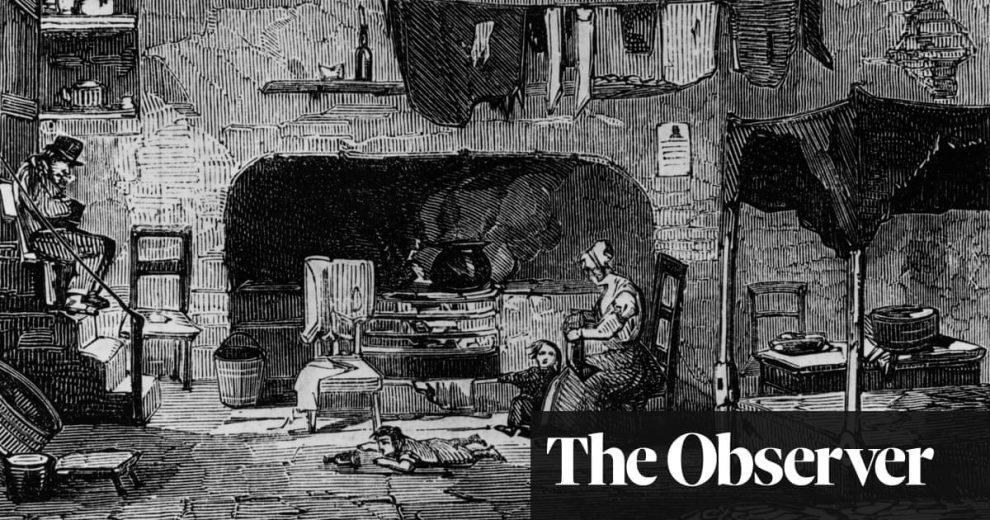

They were destitute, their children were starving and their short, pitiful lives were often marred by heartbreak and suffering. But they knew that, morally, they had rights, and they understood how to make their voices heard.

Now, previously unpublished letters of penniless and disabled paupers living in the early 19th century reveal the sophisticated and powerful rhetoric they used to secure regular welfare payments from parish authorities, despite being barely able to read and write.

The letters, which were sent to the overseer of Kirkby Lonsdale parish between 1809 and 1836, demonstrate how poor families were “masters” at navigating the complexities of the Old English Poor Law and negotiating effectively for long-term financial support.

“It’s the closest you can get to an oral testimony [of these paupers] in the historical record – we think almost all of these letters were written by the people who signed them,” said Steven King, professor of economic and social history at Nottingham Trent University.

In some letters the paupers write phonetically and in their Cumbrian dialect – exactly as they would speak the words they are writing. “Some of these people talk as if writing inflicts pain. They have to navigate a medium with which they are wholly unfamiliar. They are literally writing from sound,” said King.

Paupers were forced, through sheer desperation, to write such letters when they became destitute after moving away from their home parish. This is because, under the Old Poor Law, those in need were only allowed to ask for financial assistance from the rate-payers of their home parish and not simply the parish they were living in. Often, it was only by writing humbly to the overseer of their original home parish and demonstrating why, morally, they “deserved” his help that impoverished families could get any relief at all.

“The system makes it difficult for them [to get support], just like the modern welfare system makes it difficult for people,” said King. “They have to find a way – and that’s what they do.”

For example, the rhetorics of “nakedness” and “starvation” are deployed with great effectiveness by several different correspondents, such as when one parishioner writes: “The children are all nearly naked and starving.” This would have been seen as immoral and “an affront to dignity”, according to King: an overseer could potentially lose his moral standing in the parish by ignoring such a letter. Another wrote: “I hope you will befriend me at this time or it is up with me on all sides.”

“These people have no legal rights – but they are very adept at asserting moral obligations, particularly if they’re disabled,” said King. “They are not powerless. They may use supplicatory language every now and again – ‘I’m your humble servant and I’m very sorry for writing’ – but what they mean is: ‘Give me the cash.’”

The letters will be published by the British Academy on Christmas Eve in a new book, Navigating the Old English Poor Law, by King and Dr Peter Jones, research associate at the University of Leicester. In total, the two academics analysed 599 pieces of correspondence relating to just 20 poor families from Kirkby Lonsdale. This enabled them to understand not only the rhetorical strategies the paupers employed to convincingly negotiate on their own behalf, but also how they often managed to get friends, advocates and doctors to argue their case and emphasise the moral legitimacy of their claim for support.

One man, who got a splinter in one eye while working in a lime kiln and had a cataract in the other, “pulls every moral lever to get as much welfare as he can”, says King. “You see the way in which he uses his own words, official words and the words of advocates to make a case. And, of course, they give in – they pay his rent and give him an allowance, because he has a moral case. What can you do if a man is blind? You can’t let him starve to death.”

Jones said the letters have made him consider how moral rights are framed within today’s bureaucratised, nationalised welfare system and pity the benefit assessors who, unlike the parish overseers of the past, have no discretion and little power.

“It’s become more and more difficult now for the agents of welfare – the workers who are on the frontline, dealing with the poor – to treat the people in front of them as moral individuals whose needs must be interpreted and responded to. That’s something we’ve lost.”

This content was originally published here.

VOTA PARA EVITAR LA DICTADURA

SALVA Al EDOMEX, UNIDOS SOMOS MAYORÍA

TENEMOS SOLO UNA OPORTUNIDAD

EL 4 DE JUNIO DEL 2023 VOTA PARA MANTENER

TU LIBERTAD, LA DEMOCRACIA Y EL RESPETO A LA CONSTITUCIÓN.

SI NO VOTAS PROBABLEMENTE TU VOTO NO VOLVERÁ A CONTAR

UBICA TU CASILLA AQUÍ

EL 2 DE JUNIO DEL 2024 VOTA PARA MANTENER

TU LIBERTAD, LA DEMOCRACIA Y EL RESPETO A LA CONSTITUCIÓN.

VOTA POR XÓCHITL

Comentarios